Four Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About Gender and Pronouns

Four Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About Gender and Pronouns

by Cara Giaimo

Language plays a huge part in how we understand and describe the world around us, and how we communicate that understanding to others. Because of this, it can be easy to forget that the dictionary isn't some infallible, unchangeable document handed down from on high— but it isn't! Words are actually tools created by humans to help with those aforementioned jobs. The version of the English language that most of us grew up using has pronouns that refer to two particular genders because it reflects a culture that has also, historically, only recognized those two genders. And as our cultural understanding of gender expands, our language expands too, in order to make room for it.

It can be easier to take all of this in—and to see gendered pronouns as culturally created—if you're aware of their history. So, without further ado, here are Four Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About Gender and Pronouns!

1. "Gender" was a grammatical term before it meant anything else. When you hear the word "gender," the first thing that comes to mind is probably the cultural definition — put most simply, "the characteristics that a society delineates as masculine or feminine." But the word wasn't used that way regularly until the 1950s. Before that, it was actually a linguistic term. About one-fourth of the world's languages—German, Spanish, and Icelandic, to name a few—have what's called grammatical gender, which means their nouns are sorted into different categories called genders.

And although many of these gender categories fall along a masculine/feminine/neutral divide (as in, for example, Spanish), some don't! Take Dyribal, an aboriginal Australian language with only a few dozen native speakers left. Dyirbal has four grammatical genders, which linguists refer to as male, female, edible, and inanimate, but even that is pretty approximate. For example, Class II, the “female” class, actually contains women, fire, things related to water, things related to fighting, and most birds.

2. English used to be a gendered language.

Gendered third-person pronouns in English are the vestiges of a language that used to be entirely gendered. According to linguist Anne Curzan, Old English indicated grammatical genders using suffixes (think "-o" vs. "-a" in Spanish). Old Norse did the same thing, but used slightly different suffixes than Old English. When the Vikings began invading Northern England around the late 11th century, speakers of both languages were running into each other a lot, and probably trying to communicate. Since the two languages had a lot of roots in common, in order to understand each other better, “people may have deemphasized these inflectional endings, which were already weak, and then maybe they just dropped away,” taking their grammatical gender signification with them. The only gendered words that stuck around? Those pesky third-person pronouns, which were too short to be affected.

3. Gender-neutral and nontraditional pronouns have their own rich and varied history.

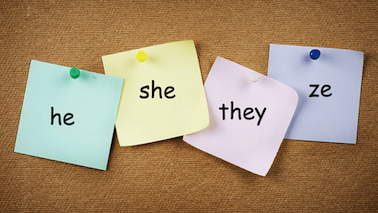

English speakers of all stripes have long been frustrated with the language's lack of gender-neutral pronouns. A look back at press records reveals public complaints from, newspaper copyeditors wrestling with inelegant phrasing, as well as police commissioners who were unsure whether or not they could arrest women under a law that only used masculine pronouns. Feminists as far back as 1882 disliked the standard practice of using "he/him/his" as a fallback pronoun, and advocated for a gender-neutral word instead. Those who noticed these problems often provided alternatives. For example, in 1884, a lawyer named Charles Crozat Converse proposed the word "thon," which was popular enough to make it into several dictionaries. Casey Miller and Kate Swift, who have written several groundbreaking works on gender-biased vocabulary, suggested "tey." More recently, people who identify outside the gender binary have resurrected some of these terms for their own personal use, as well as coming up with others. Some of the most common include "ze," "e," and the singular "they," but the sky's the limit—here's the most complete list I've found.

4. Using someone's preferred pronouns really makes a difference.

If you think about it, a pronoun serves as a synopsized version of a person, and no one wants to be condensed down to the wrong essence. Respecting someone's pronouns—by asking which ones that person prefers, using those consistently, and apologizing if you slip up—is a great way to show that you respect who that person is. As Lauren Luben recently shared in zir "Why Change Names and Pronouns?" video, "when someone uses a gender-neutral pronoun, I feel like they are identifying who I am as a being." Another person I spoke to told me that “I could give you a precise list of every single genderstraight ally I’ve ever witnessed using my pronoun correctly—that’s how much it means to me." Still others have said that being referred to correctly makes them “absolutely giddy with joy,” “so completely happy,” and "makes me suddenly want to hug them."

Learning any new vocabulary word can be challenging, and incorporating it into your daily speech might take a little while. But in the end, it's worth it, because knowing and using that word has broadened your understanding of the world, as well as your ability to describe and communicate that understanding. Non-traditional pronouns are no different!

For more information on the history of gender and grammar, I invite you to check out my three-part series at Autostraddle, as well as Gretchen McCullough's recent piece for The Toast.

Cara Giaimo is a Boston-based writer interested in words, gender, and the push-pull of identity construction. She also likes rock'n'roll and biking around. You can find more of her work at Autostraddle and Case Magazine.

My student started using they/them pronouns, but not all teachers are supportive. What do I do?